The Audacious, Comical, Tragic and Potentially Redemptive Story Of A Small Town, A Pool And The World’s Best Surfers

Pennsylvania Amish country was the unlikely setting for the first-ever pro surfing contest held in a wave pool. Was it a comic low point for the sport? Or a glimpse of the future?

By DAN FITZPATRICK

ALLENTOWN – One of the most audacious publicity stunts in the history of sport took place in an amusement park just beyond the outskirts of this quiet Pennsylvania town.

Was it a failure? Or a triumph? It’s still not clear, 33 years later. And that’s what makes it important.

Promoters called it the World Inland Professional Surfing Championship. The concept was this: 70 of the world’s best surfers would leave their traditional ocean surroundings in Hawaii or Australia or Japan for a rural section of Pennsylvania best known as a refuge for men and women who dress modestly, favor simple living and like to bake sweet pies filled with molasses and brown sugar.

It was the first-ever professional surfing contest held in a chlorine-filled pool. (see video for rare event footage) The nearest beach was 90 miles away.

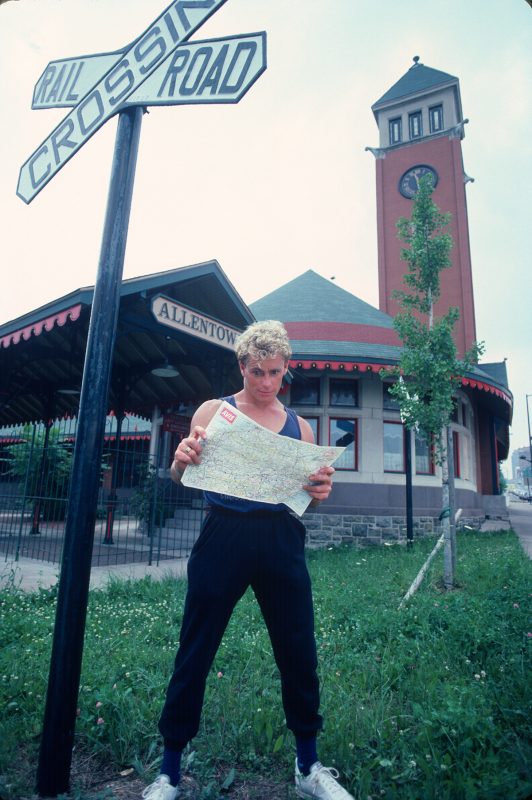

Tom Carroll in Allentown, 1985. Photo: Robert Beck

To those involved the stakes were incredibly high. The hope for tour organizers was to broaden the appeal of the sport and set up a chain of wave pool contests throughout middle America. The hope for Lehigh Valley officials was that the event would put it on the map at a time when jobs in the region were beginning to dry up. The hope for the host venue Dorney Park and its fitness fanatic owner Robert Plarr (see video for a shirtless Plarr leading one of his Dorney Park aerobics classes) was that it would justify an outlay of $7-10 million. (See our exclusive oral history for more detail) (See our video for a quick tour of Allentown today)

The gambit worked in the short term. The novelty of the event did in fact place surfing on the U.S. landscape for a season, a feat in a country that largely ignores the sport. Allentown got its publicity, even if some of it was inaccurate. People magazine mistook Allentown for Bethlehem (home to Bethlehem Steel) with its headline: Cowabunga! Surf’s Up In A Pennsylvania Steel Town. (see video for aerial footage)

But the surfers and media that followed the sport closely had a more skeptical view of the proceedings. “These waves could have only been described as pitiful,” said Matt George, a journalist who covered the 1985 event and now is the editor of Surftime magazine in Bali. “It was like if you wanted to have a [Formula 1] race and it was for children’s bicycles. It was doomed from the beginning.” As one South African surfer who participated, Shaun Tomson, put it: “The wave was crap.”

These wave pools at the time were just goofy as hell and they were right next to Captain Blackbeard’s soapy sudsy bubble ride. They were ridiculous to us.

For a certain segment of surfers Allentown in the intervening decades evolved into a parable that represented either a comic low point — (Stab magazine in 2015: The event “brought surfing to its knees” . . “all in front of a crowd of next to no one” . . .as competitors “were forced to grovel across 2.5-second-period chlorinated slop for points”) — or the reckless pursuit of artificiality, consumerism and middle American squares.

The wave, Allentown, 1985

For others it became something else: a lost opportunity. It was clear pro surfing would not become as big in America as baseball or football or basketball. “That was always the dream,” said Tomson, a former world champion. “All we need to do is to show mainstream America what an amazing sport lifestyle we have. But Dorney Park wasn’t really part of the plan. The dream of man made waves burst at Dorney Park.”

Kelly Slater’s Surfing Machine. Illustration: Alvar Sirlin

Allentown, which sits roughly 90 miles west of New York City, was never used to this much scrutiny from the outside world. It’s far enough from major U.S. cities that the first American army chose to hide the Liberty Bell here from the British during the American Revolution. It later became a refuge for German-speaking immigrants who were attracted by the state’s reputation for religious tolerance. Horses, carriages and buggies belonging to the Amish are still a common sight on local roadways.

Even a brief turn in the popular culture – Billy Joel’s 1982 song “Allentown” – was a source of unwanted attention. Residents say the paean to blue-collar decline was actually about Bethlehem, the next town over.

“The world had the wrong impression of Allentown because of Billy Joel’s inaccurate song,” said Ricki Stein, who covered the 1985 event for the Allentown Morning Call.

Today Dorney Park still stands just over the Allentown border, in South Whitehall Township. The same wave pool used in 1985 is still there, as part of the Wildwater Kingdom, but no surfing is allowed. There are no visible signs that the event took place, nor is there any record of it at the local historical society. No one seems to care. On a hot day last summer scores of kids and adults bobbed in the pool and shouted with delight once the machine cranked up the waves.

A new consideration of what happened here in 1985 is critical if you want to understand the hype surrounding the recent public debut of a wave pool on the other side of the country, in Lemoore, Calif. It was built by Kelly Slater, an 11-time pro surfing champion. Slater, who was 13 when Allentown happened, inadvertently developed the Surf Ranch as Allentown’s antithesis.

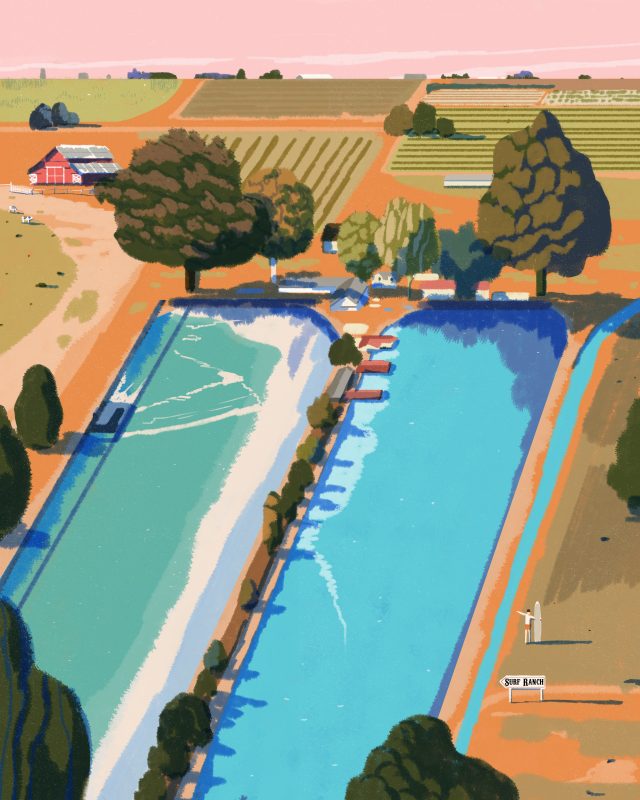

Kelly Slater in front of his creation in Lemoore, Calif. Photo: WSL

Where Allentown was unable to provide pro surfers with crumbly waves higher than 3 feet the Surf Ranch is a high-performance canvas designed to mimic the power and speed of the ocean. Where Allentown was open to the public from the very beginning, Lemoore has been a tightly-held secret, cordoned off behind a brown fence. Until this weekend it was mystery even to those who lived across the street.

Spectators taking in the action at Allentown in 1985. Photo: Robert Beck

Much is once again at stake, just as it was in 1985. The World Surf League, which owns the Surf Ranch, views this pool and its technology as a way to control the vagaries of the ocean and design a viewing experience pleasing to a broader audience (the hazards of this approach became clear during a competition on May 5 when the wave machine shut down for 56 minutes due to “maintenance” and “technical issues.”) The league wants to build these pools across the U.S. (one is already underway in West Palm Beach, Fla) and around the world (the WSL’s goal is to integrate a pool into the 2020 summer Olympics in Japan).

Filipe Toledo, at the Surf Ranch,, shows what is possible on an artificial wave with more power. Photo: WSL

“Stadium surfing,” said WSL Chief Executive Sophie Goldschmidt at a Surf Ranch press conference in early May. “Who would have thought?”

We spoke to many people who were at the Allentown event in 1985, some of whom are among the lucky few who have tried Slater’s wave. They say the technology has finally caught up with the vision of 1985. It’s clear, they say, that Lemoore would not have happened if not for the carnival of Allentown. Slater has provided Allentown – and those who conceived it – with new relevance.

Our view of The Surf Ranch

“This is exactly what I imagined,” said former pro surfing tour head Ian Cairns, who organized the 1985 event.