Surfer in Chief

Why Richard Nixon Is Responsible for One of The World’s Greatest Waves

BY ALEX ROTH

Back when Southern California’s best surf break was off limits to everyone but the military, teenager Bob Mardian and a friend were surfing the spot when his buddy wiped out and lost his board. Marines waiting on the beach seized the board when it washed up on shore, put it on a military vehicle and whisked it away.

A few days later, Mardian, his friend and his friend’s mother went to the Camp Pendleton Marine base to retrieve the 10-foot Hobie, which was being held captive in a giant warehouse along with dozens of other boards that had been confiscated over the years. Both the kid and his mother were commanded to sign various official documents.

“He had to promise, ‘I’ll never surf here again, I’ll sign away my future children, blah blah blah,’ Mardian, 69, recalls. “They told him he wouldn’t get the board back if it happened a second time. It was all very solemn and serious.”

One man ultimately ended these standoffs: Richard Nixon.

The 37th President of the United States has many legacies, of course. A particularly obscure one is his decision to turn a small coastal section of Camp Pendleton roughly 50 miles north of San Diego into a state park. As a result of his decision, the break known as Lower Trestles — with its consistent, peeling waves and occasional perfect barrel — has become one of the world’s iconic surf spots.

No more need for surfers to sneak to the ocean through head-high reeds while eluding military patrols. No more confiscated boards. In 2013, CNN, working with a group of Surfing Magazine editors, named Trestles the 12th-best surf spot on the planet. Every September, the site plays host to the Hurley Pro, one of the world’s most prestigious pro surfing competitions.

What motivated Nixon to create San Onofre State Beach, opening up Trestles to the world? Like many stories involving the only U.S. president to resign from office, this one involves political calculations, feelings of betrayal and possible ulterior motives.

Richard Nixon’s true motivations for opening Trestles to the public remain a bit of a mystery. Photo: Richard Nixon Presidential Library and Museum

If the military wasn’t happy about Nixon’s decision — and they weren’t — there was another group of people even less happy: The San Onofre Surfing Club, a private group that had been granted exclusive access by the Marines to a section of the beach 1.5 miles south of Lower Trestles.

To this day, some members of the club speak in wistful tones about Nixon’s decision.

“Were we all upset that we had exclusive access to our beach and then suddenly we didn’t?” said Brian Ephraim, the club’s current president, who was a kid during Nixon’s first term. “Well, yeah. Wouldn’t you be?”

San Onofre State Beach runs along a 3.5-mile stretch of sand and ocean on the northern border of San Diego County, from a spot now known as Upper Trestles to a section just south of the San Onofre nuclear power plant.

In 1942, during World War II, the Marines acquired 123,000 acres of land in that area — including that stretch of beach — and created Camp Pendleton, which remains the largest Marine base on the West Coast.

From then until Nixon’s presidency, which began in 1969, the Upper and Lower Trestles surf breaks were a forbidden zone for surfers. Nonetheless, plenty of locals found it impossible to resist the lure of Trestles’ glorious waves. And so began a quarter century of cat-and-mouse battles between surfers and Marines.

Back then, surfboards had no leashes, so every bad wipe-out carried with it the potential that your board could float off into captivity. Sometimes surfers would try to retrieve their property from the base, sometimes they wouldn’t bother. Exactly what happened to all the abandoned boards lining the walls of that cavernous military warehouse remains something of a mystery.

For a few dozen lucky families, however, membership in the private San Onofre Surfing Club meant they could still surf along a prime section of beach just south of Trestles. In the early 1950s, the Marines granted the club exclusive access to that section of the beach in exchange for the club’s promise to maintain it. The surfing in that area is good, but not Trestles-level good.

To get to Trestles, surfers who weren’t members of the club would often sneak to the beach via a series of well-worn makeshift paths concealed by tall reeds at the northern end of the base. Once you reached the sand, you’d scan for any military patrols, then make a dash for the ocean with your board under your arm.

If you were a member of the club, however, you could paddle the 1.5 miles from your private beach to Trestles — still an illegal act but sometimes an easier mission. Then Nixon became president. Upon taking office, he bought an oceanfront estate in San Clemente, 40 miles from his birthplace of Yorba Linda. He stayed at his new place frequently during his presidency and it became known as the Western White House. His new home was a short stroll along the beach from Trestles.

President and Mrs. Nixon enjoy a walk on the beach near the San Clemente “Western White House” Photo: Richard Nixon Presidential Library and Museum.

From the beginning, members of the San Onofre Surfing Club found Nixon’s presence an inconvenience. His visits to the Western White House meant extra security on the base along with Coast Guard cutters off shore, making it even more challenging for surfers to sneak to Trestles via land or sea, according to Mardian, who lives in Dana Point and owns several restaurants.

And then Nixon, or someone close to him, came up with an idea that changed everything.

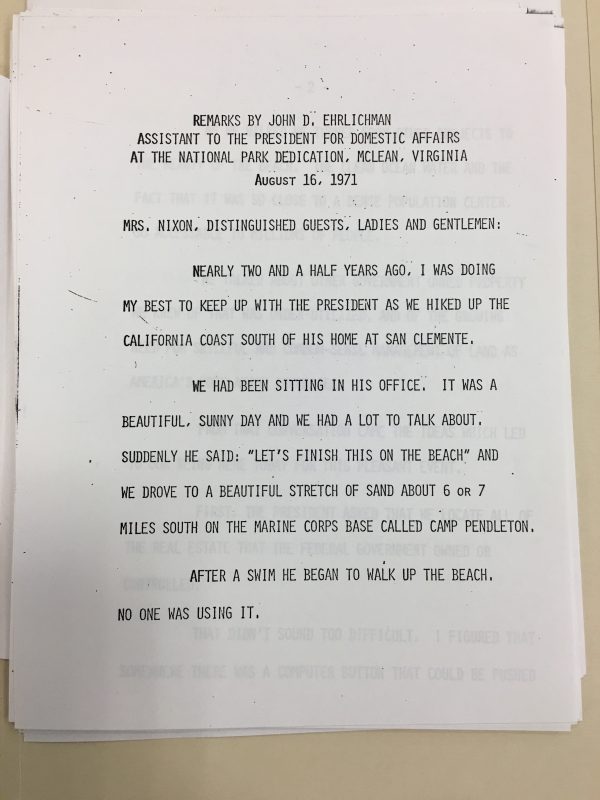

As recounted by John Ehrlichman, one of Nixon’s closest advisors, he and Nixon were taking a leisurely walk along that stretch of sand one day when Nixon, entranced by the beauty of the location, first floated the idea of converting large swaths of federal land into state parks.

“As we walked, he turned from other subjects to the beauty of the beach,” Ehrlichman said in a 1971 speech. “The clean ocean water and the fact that it was so close to a dense population center. So accessible to millions of people. He talked about other government-owned property he knew of that was under-utilized, and of the growing need for skillful and common-sense management of land as America’s population increases.”

Maybe that particular conversation happened exactly as Ehrlichman describes, maybe it didn’t. Either way, what’s clear is that Nixon, even at this early stage of his presidency, was looking to create a lasting domestic legacy.

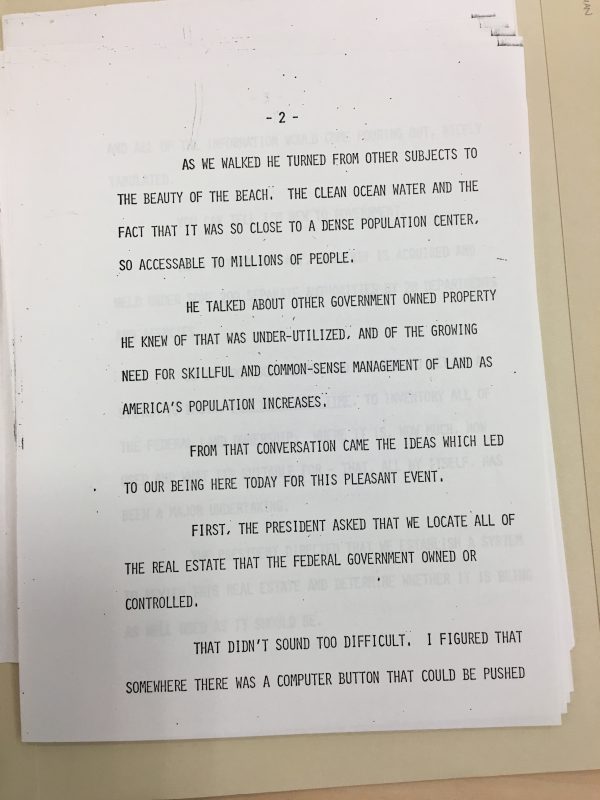

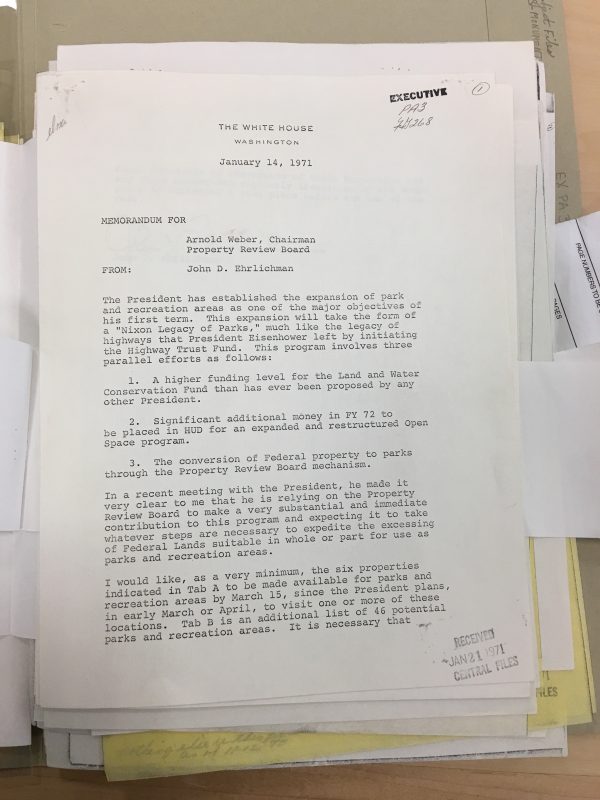

In a Jan. 14, 1971 memo on file at Nixon’s presidential library in Yorba Linda, Ehrlichman declares that “the expansion of park and recreation areas” will be “one of the major objectives of (Nixon’s) first term.” In the memo, Ehrlichman envisions a Nixon legacy comparable to “the legacy of highways that President Eisenhower left by initiating the Highway Trust Fund.”

Text of John Ehrlichman’s speech

“As we walked, he turned from other subjects to the beauty of the beach.”

The John Ehrlichman memo at the Richard Nixon Presidential Library and Museum.

At the time, this endeavor also made political sense, according to Boyd Gibbons, who served on Nixon’s Council on Environmental Quality.

Gibbons, 78, who now lives in Spring Green, Wisconsin, noted that large numbers of voters in both major parties had become alarmed about the environment. In 1969, Ohio’s Cuyahoga River caught fire because it was so polluted. That same year, one of the largest oil spills in the nation’s history, off the coast of Santa Barbara, had a cataclysmic impact on marine life.

Given the nation’s mood on this topic, Nixon recognized that becoming a champion of open public space, and environmental issues in general, could have distinct electoral benefits. Gibbons wound up serving on a task force whose mission, according to a memo on file at the Nixon library, was to “break loose excess federal lands for parks.”

“Nixon saw the politics of it,” Gibbons recalled. “And I think that Ehrlichman helped him see that.” The administration eventually compiled a list of several dozen properties around the nation, many of them on military land, that should be converted to parks and open space.

The Trestles beach was on the list from the very beginning — in part, perhaps because of local political considerations as well. A 1971 issue of Surfer Magazine contends that Nixon was trying to help the re-election prospects of U.S. Senator George Murphy of California, a fellow Republican, who could publicly champion the proposal and use it as “an ideal vote-getting issue” by positioning himself as a “conservationist and beach lover.”

It wasn’t long before Nixon’s plan came to the attention of the San Onofre Surfing Club. As it so happened, one of the club’s original members, Robert Mardian Sr., was also a lawyer in the Nixon administration, eventually serving as assistant attorney general. (His son, Bob Jr., was the one fond of sneaking into Trestles.)

Mardian arranged a meeting between Nixon and some members of the club. That meeting took place on Aug. 25, 1970 at the Western White House, on a lawn with a spectacular ocean view. Photographs were taken. The event lasted only a few minutes, during which Nixon was presented with an honorary membership to the San Onofre club.

Nixon receiving an honorary membership from the San Onofre Surfing Club on Aug. 25, 1970. Photo provided by Bob Mardian Jr.

Today, members of the club who met Nixon that day have differing recollections of what they hoped to accomplish by making Nixon an honorary member. (The senior Mardian died in 2006.)

Denise Tkach, who was 17 at the time, is now a 63-year-old retired healthcare professional who still lives in Dana Point.

“They gave him an honorary membership in hopes that he wouldn’t make it public — that was the whole premise,” she recalled. “And then he did it anyway. And we were all very disappointed.”

Tom Turner remembers things differently. He says the club recognized at the time that its days of exclusive beach access were numbered. Even before Nixon devised his plan, the club faced pressure from the local community and some members of Congress to open up the beach.

Turner, now an 85-year-old Palos Verdes real-estate investor, says the club simply hoped to maintain a good relationship with the president so they might have some input on some of the specifics of his proposal.

“I suspect that those of us who were realists thought it was inevitable” that the beach would become public, he said.

And they were right. Seven months later, Nixon issued a press release: six miles of beach on Camp Pendleton, including Trestles and the San Onofre Surfing Club’s private spot, would be transferred to the State of California for “public recreational use.”

Even after that public announcement, however, Nixon faced resistance from the military, who disdained the notion of surrendering any of its land. The Nixon administration eventually turned numerous military parcels from Oregon to Michigan to New Jersey into public parks — and “it was a bloody fight for every single one,” Gibbons recalled.

The famous Nixon tapes on file at his presidential library include a brief discussion of this thorny topic during a May 20, 1971 Oval Office meeting that included Nixon, Ehrlichman and George Shultz, then the director of his Office of Management and Budget.

“We’re having problems with the Armed Services Committee in shaking some of this military land loose,” Ehrlichman says on the tape. “(Committee chair U.S. Rep. F. Edward) Hebert’s giving us an unmitigated hard time on Camp Pendleton.”

Ehrlichman goes on to mention that Herbert sternly told a member of the Nixon administration, “Don’t do it.”

But Nixon went ahead and did it anyway. Under prodding from his administration, the Marines soon leased the land to the State of California for 50 years.

Today, Nixon’s work to create more public recreation space — much of it in or near urban areas — remains an admirable if little-remembered part of his legacy, as does his work on behalf of other environmental issues. It was Nixon who created the Environmental Protection Agency and the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. It was Nixon who successfully supported passage of the Clean Air Act, the Clean Water Act and the Endangered Species Act.

Nixon opened the military land to the public despite many objections to the move. Photo: Richard Nixon Presidential Library and Museum.

Texas A&M Prof. Luke Nichter, co-author of the New York Times bestseller The Nixon Tapes: 1971–72, said Nixon was motivated by a combination of shrewd political instincts and a genuine concern for environmental issues, a concern that predated his presidency.

Few people realize how much Nixon accomplished in this area, Nichter noted, partly because of “political fault lines both during Nixon’s time and today.”

On. Aug. 9, 1974, Nixon became the first U.S. president to resign from office. Ehrlichman spent a year and a half in prison for his role in the Watergate scandal.

Last year, an author named Anthony Clark wrote a book claiming Nixon’s entire parks program was simply a cover for an illegal, if ultimately unsuccessful, plot to build an ocean-view presidential library in San Clemente. Prying that land loose from Camp Pendleton would help Nixon accomplish this task, Clark’s book argues. Several prominent Nixon historians have dismissed Clark’s thesis, one labeling it “totally implausible.”

The San Onofre Surfing Club still exists. Its mission includes making “responsible recommendations to the Department of Parks and Recreation pertaining to the operation and development of the San Onofre Surfing Beach, and to seek to retain the beach in its natural state.”

The club has been remarkably successful in its efforts. The parking lot remains unpaved. Still standing is an old shack built decades ago, its thatched roof made of woven

palm fronds.

You can get to the beach, still leased by the State of California, by paying a $15 entrance fee at the guard shack at the top of a small road that winds down to surf breaks named The Point, Old Man’s, and Dogpatch. No private club membership badge required.

Richard Nixon illustration by Xiao Hua Yang