Chitty Chitty Bang Bang

What happened the very first time surfers competed in a wave pool? Hint: It did not go well. Those who were there describe the scene in their own words.

By DAN FITZPATRICK

When Kelly Slater unveiled his central California surf machine to the public this year, promoters and reporters marveled at the novelty of riding a wave 100 miles from the nearest beach. Many asked: Could this finally open up the sport of surfing to a wider audience?

What few mentioned is this all happened once before – in 1985, on the other end of the U.S. And that it did not go well.

Those who were there to witness the scene in rural Pennsylvania helped Twenty Magazine reconstruct the oral history of an audacious scheme that was either a comic low point for the sport or an entrepreneurial gambit that made other successes possible. (see here for more on that debate) They also provide their diverging theories of why it took so long to happen again.

Before getting to all that it helps first to know the motivations of three people who were largely responsible for bringing the optimistic-sounding World Inland Professional Surfing Championship to the heart of Pennsylvania Amish country (see this video for rare footage of the contest). They were united by a mix of chance, hope and cunning.

Robert Plarr, a former Marine and reconnaissance diver, was looking for a way to replicate ocean training inside his family’s sprawling Dorney Park amusement complex. Ian Cairns, a former surfing champion who was in charge of the world surfing tour, was looking to improve his contests by eliminating the unpredictable elements offered up by the ocean. The Allentown, Pa. native who brought Plarr and Cairns together, Jim Karabasz, was a recreational surfer who believed a series of wave pools would eventually proliferate across middle America.

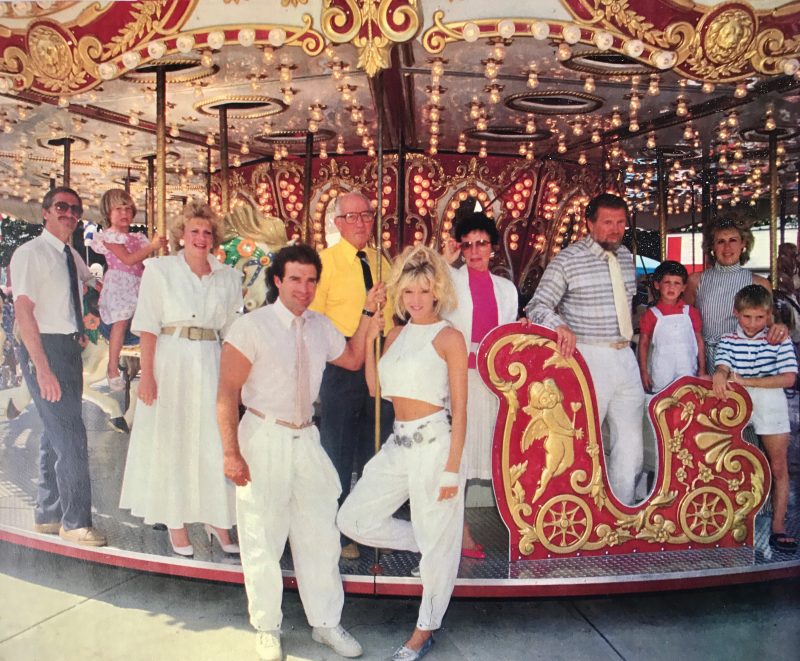

Robert Plarr and his wife stand in front of the Dorney Park carousel with other members of their family

Robert Plarr: I was a loose cannon. When I got out of the Marines I said I want to build a wave pool. Everybody was against it.

Jim Karabasz: One day I saw an advertisement for Dorney Park. They were going to build a wave pool and they wanted to go surfing. I was like ‘wow that’s a cool idea.’ So I met with Bobby Plarr, and we sat down. He had a vision but had no idea how to implement it.

Robert Plarr: I said, ‘Find the guy to do it.’

They said it’s going to bankrupt the park.

Jim Karabasz: I got in touch with Ian Cairns who was the head of the ASP, which is the predecessor of the current pro surfing group. Lucky for me Ian was a very open minded guy and saw what new possibility there was to move surfing away from the coasts and move it to where the populations were.

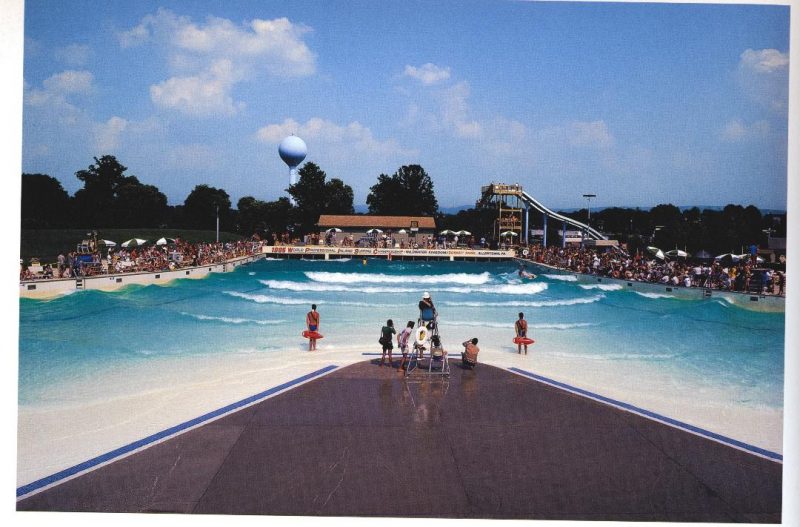

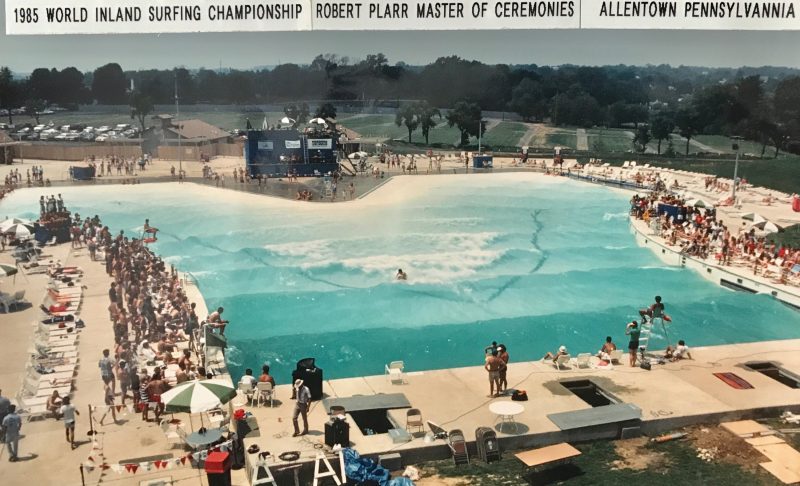

The wave, 1985

Ian Cairns: I have always been intrigued with the idea of making waves.

Jim Karabasz: There was a lot of discussion of what could and couldn’t be done. Bobby’s commitment to having a surf-able wave was the driving force. He wasn’t taking no for an answer; he wasn’t backing down.

Ian Cairns: I flew out there to Pennsylvania, met with the owner, looked at the wave and I thought it was worth a shot. Why not let’s have a go? Let’s see what we can make work.

I don’t know who was hoping for 7 foot waves but somebody had better drugs than I had.

Jim Karabasz: Back then I believed that every park would put one in and in 5 years there would be an inland pro tour. There would be more money in it because you could go to a TV production company and say it is going to happen at this time and will end at this time.

Should we discuss that this might unravel the universe as we know it?

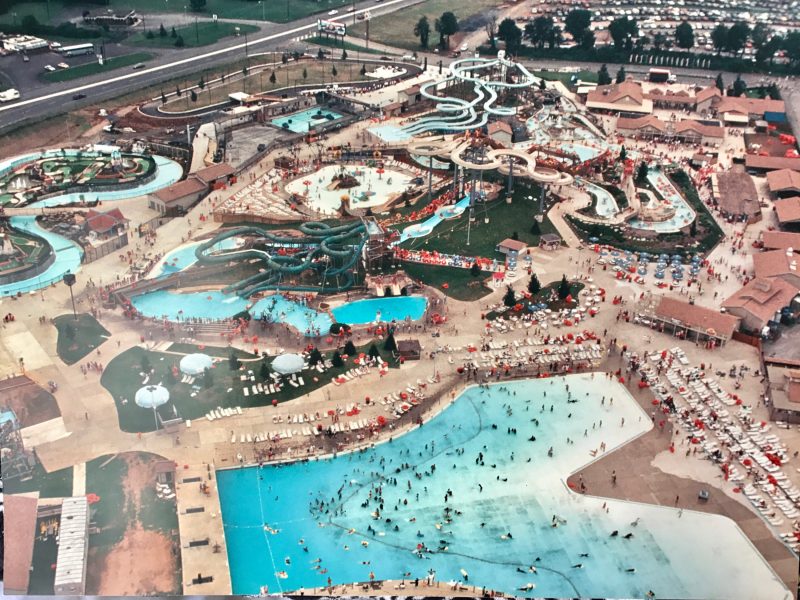

The scale and novelty of the project immediately divided the family that owned Dorney Park, which sat just outside the Allentown border in South Whitehall Township. (see this video for an aerial view) Plarr – who started working at the park at age 7 and did everything from sell popcorn to clean toliets – borrowed the money needed to build the new water park by using some of the Dorney Park land as collateral. One of his family members was so against it that he sold his interest in the park weeks before the pool opened. (see this video for a history of the park)

Dorney Park from above, 1985. Photo: Robert Beck

Robert Plarr: They said it’s going to bankrupt the park. I said we are going to sell this place for about $50 million in five years. They laughed and walked out.

For Plarr it was the latest in a long line of experiments that puzzled those around him. Before the pool he built an underground home (see video)and windmills (see video) for creating electricity. He created a health restaurant (Eat To Win) that served people with diabetes or heart trouble; it listed calories and sugar content years before that was a thing. To keep fit he he taught aerobics classes that reportedly attracted 1,000 women a night (see video here; Plarr is the shirtless one in front) and climbed coasters so he could do pull-ups 100 feet in the air. His nickname: “Rambo.”

Plarr’s extreme interest in fitness, he said, can be traced back to a tragedy that he did not wish to repeat. He was 15, he said, when his father died in his arms. The unexpected death also thrust him into a leadership position earlier than expected. The park had been in his family since the time of his grandfather, a one time Philadelphia butcher.

There was none of that “surfing is art, not sport” bullshit.

While Plarr tried to drum up publicity for the 1985 contest with TV ads and “Surf Pennsylvania” billboards, the country’s top surfing journalists decided they would cover the event partly because top surfers had agreed to show up. They approached the subject with a considerable dose of skepticism. Surfer magazine sent writer Matt Warshaw, writer/photographer Matt George and photographer Robert Beck.

Matt Warshaw: I was 25, and associate editor. I’d been on the job just six months when the Allentown gig came up. What I do recall is that Matt George and I, at that point in years to come — all the way till today, for that matter — were pretty dissatisfied with a lot of the events, and how pro surfing was being handled in general. We were both huge fans, understand. We both loved competition, there was none of that “surfing is art, not sport” bullshit. We just wanted the contests to be better. We hated the Op Pro, and really hated the idea of having an event in a wave pool.

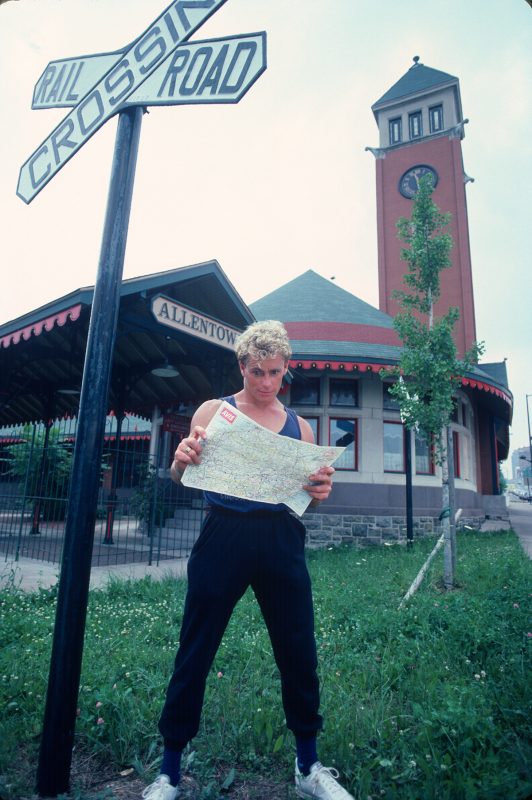

Matt George, left, and Matt Warshaw, right, on site in June 1985

Matt George: The conversations went like this: ‘What a load of bullshit this is going to be.’ The basic feeling surfers had up until Kelly’s extraordinary achievement in Lemoore was yeah we will ride one of these corny wave pool things but it felt like letting your dog drag you by the skateboard down the board walk of the beach. These wave pools at the time were just goofy as hell and they were right next to Captain Blackbeard’s soapy sudsy bubble ride. They were ridiculous to us.

Chitty Chitty Bang Bang

The pool itself was heart shaped, with waves breaking to the left and right. The machine was powered by for large steel flaps that pushed more than 100 tons of water across an expanse of 50 meters. The water was 12 to 15 feet at its deepest.

There was some discussion in the newspapers at the time about how the system would vary wave heights from two feet – “more fit for a beginner” – to 7 feet, “which is what an expert needs for high performance surfing.” There is still some confusion and debate about this. No one I talked to acknowledged that 7 feet was a real possibility so it’s hard to know if that was talk was hype or if the technology failed to produce what it promised.

I was a believer, man, which is why the disappointment was so powerful.

Jim Karabasz: I don’t know who was hoping for 7 foot waves but somebody had better drugs than I had. You couldn’t produce a 7 foot wave. The pool would have had to be deeper and longer. It was designed to create a 3 foot wave every 3 and a half seconds. I was in every meeting and nobody discussed 7 foot waves.

Trying to play by the rules in Allentown, 1985. Photo: Robert Beck

The event attracted many of the top surfers in the world, from Australia’s Tom Carroll to South Africa’s Shaun Tomson to Santa Barbara’s Tom Curren. Many did not know what to make of the wave, the park or the town. Some didn’t know their surfboards would have a harder time floating in pool water, which lacked the buoyancy that salt provides in the ocean.

Matt George: We were all standing around that pool in Allentown, the elite of the surfing sport, and they turned on that machine and those first waves rolled down toward the shallow end , toward us, the collective howl that went into the air, from the elite, probably could have been heard in New York. No it was not a howl of stoke. It was a howl of laughter. These waves could have only been described as pitiful.

It reminded me of Chitty Chitty Bang Bang. That’s what we called the wave machine because it would go cha-chunk cha-chunk cha-chunk cha-chunk cha-chunk.

Shaun Tomson: It was a case of reality not really meeting our expectations.

Jim Karabasz: A third of them came to do business. They had the proper equipment, the proper mindset. They were like ‘ok this is like a really bad day at my local break.’ A lot of them told me that. Then there were a lot of them that showed up and were completely unprepared. They were quickly eliminated from the contest and they hung around for days basically bad mouthing the whole wave pool to anybody who would listen.

Tom Carroll trying to find his way in Allentown, 1985. Photo: Robert Beck

Matt George: I remember when we had our first meeting about the rules. The bewildered look of these surfers who didn’t know what to ask. Cheyne (Horan) raised his hand. ‘Ian, should we discuss that this might unravel the universe as we know it?’ There was dead silence for about 7 seconds.

Robert Beck: I remember first walking out on the deck and thinking that it was pretty small. Not only was the wave very machine like and kind of mundane but the surfing was as well just because of the size of the wave and the shape of the wave. Everybody basically did the same maneuver in the same place.

Jim Karabasz: Even though I talked to a whole bunch of them long before they came and tried to explain that fresh water is a lot less buoyant than salt water and they all showed up with what they thought was their small wave boards for the ocean and a lot of them were just floundering. A lot of them bitched and moaned about it but it wasn’t for lack of knowledge.

Allentown, 1985. Photo: Robert Beck

Matt George: The machine had problems and it broke down a few times. It would overheat because we had to run it at super max just to try to catch a wave. It reminded me of Chitty Chitty Bang Bang. That’s what we called the wave machine because it would go cha-chunk cha-chunk cha-chunk cha-chunk cha-chunk. And then we could hear the alarm go off when it overheated every half hour because it was operating at super max. It was just chaos.

Was this the shape of things to come for professional surfing? Or a remarkably different and unique novelty?

Carroll won the contest, although few remember how or why. He defeated Derek Ho, a Hawaiian, in the final. More memorable to many who were there were the series of culture clashes, pranks and escapades that occurred over the course of five days. Many of them served to reinforce the distance between locals and surfers.

Matt George Wins A Hot Buns Contest

Robert Beck: This might have been either a Friday or Saturday night. It was some big kind of a shindig they were putting on for the surf contest. I believe it was in an old roller rink.The ratio of females to males was about 10 to 1. The few guys who were there looked like they just got off a job from a gas station and couldn’t care less. It was just so weird.

Matt George: The Hot Buns contest was not a political statement; it was a drunken one. Look man I can dance, and there was an opportunity in an extraordinary setting.

Ian Cairns: I have never ever looked at Matt George’s hot buns so I don’t think I would have attended.

Robert Beck: The judging was based on how loud the crowd cheered for you. Matt is a good looking guy and has a good physique but there were 90% more women than there were guys so he was going to get the most applause. Matt stripped down to his underwear. He ended up just wadding up double the size of a softball and stuffing it in his pants. And when he walks out the place just went bananas. He does a big swan dive into the crowd and he breaks his ankle.

The Hot Buns contest was not a political statement

Matt George: My ankle still hurts today. But well worth it. It was such a metaphor for how goofy this thing was.

Tom Carroll, who won the contest in 1985. Photo: Robert Beck

Ian Cairns: Back in those days you were allowed to be a character. Wild crazy shit; it’s part of the whole spirit.

Jim Karabasz: I don’t remember every detail of that and even if I did I really don’t want to get pulled in that conversation about what Matt George did or didn’t do. He did as much as he could to pull the event down as anything else.

Matt Warshaw: Matt George was the only person who could have pulled it off with that much style. He stopped, put himself in profile to the front of the stage, placed his hands on hips, jutted his pelvis an inch or two, and gave a smoldering look at the audience over this shoulder. It was as fine a piece of spontaneous comedy as I’ve ever seen. What he did was a 10 times, 100 times, more entertaining than the any of the wave-riding that weekend.

Derek Ho, who lost to Tom Carroll in the final, 1985. Photo: Robert Beck

Kong vs. Lifeguard

One confrontation that was fraught with more tension took place pool side. A lifeguard was fed up with Gary “Kong” Elkerton, an aggressive Australian surfer who was not adhering to Dorney Park’s rules.

Warshaw: It was kind of unfair. The lifeguard, a really young guy, probably in his late teens or early 20s, was just doing his job. Kong was being Kong, which meant playing to the crowd, breaking rules, “getting radical.” He went down this one huge water slide standing on his feet – you were supposed to go down on your back – which was impressive, and for sure dangerous.

Robert Beck: Gary was one of the guys who was really full of himself. He was a real wild kid.

Matt George: Gary just wouldn’t behave. ‘No running on the deck.’ He would run on the deck. He would stand up on the slippety slides. You take the best surfers in a sport known for extreme individuality, and you put them around a YMCA sized pool in Allentown Pa and tell them to do their worst and what do you think is going to happen?

It was an ugly little episode

Matt Warshaw: It was great, it was funny. The lifeguard tried to do his job, Kong laughed at him, the lifeguard got angry and flustered and said something stupid like “You’re gonna get kicked off the surfing tour!”, which of course only made Gary -and all of his henchmen, myself included – laugh harder. It was an ugly little episode, in hindsight.

Ian Cairns: Some pansy lifeguard in America? Fuck him. It’s beautiful. That’s what happened when you bring a bunch of crazy Aussies into a secluded neat little town in the middle of Pennsylvania; there is a real big cultural difference.

Jim Karabasz: The gentleman he had a conflict with was a guy named Joe Messinger. It was a conflict between worlds. Joe was doing his job. Joe in those days he stood a good 6 foot 2 and a 190 pounds. He got into a yelling match with a full grown adult who could handle himself and in the end Gary moved.

The Photo Matt George Took In His Underwear

A cope of the image taken by Matt George that ran as a double-page spread in Surfer magazine. The original has been lost.

The defining photo of the event was taken by Matt George for Surfer magazine. It ran as a double page spread. A bulbous blue water tower rises in the background, overseeing the proceedings. White and green striped umbrellas encircle the pool, offering shade to some, while some onlookers are perched at the top of a nearby water slide. A pair of lifeguards watch from the shallow end as surfer Tom Carroll is up and riding. A few puffs are in the sky and the grass is a verdant green.

Matt Warshaw: It summed up the whole surreal ridiculous thing in a single frame. I still love Matt for how he took that event on. He destroyed it by laughing at it, but not in a mean way.

It summed up the whole surreal ridiculous thing in a single frame

Matt George: I was on the judging tower at the time. I stepped out and took that shot. I shot one frame because I was in my underwear and of course everyone was looking at me. I captured the photo of my career. I have lost it. Back when you had to send slides to magazines it got lost in the mail. It captured a utterly unique moment in surfing that will never happen again.

So Why Didn’t It Happen Again?

There is a document still on file with the current owners of Dorney Park. It’s a proposal that was drawn up following the 1985 event for prospective sponsors – specifically, Anheuser Busch. The proposed price to help pay for a repeat event was $100,000. The pitch: “We foresee an even greater media response.”

Photo: Robert Beck

But it never happened. Why was there not another event at Allentown or anywhere else? Why did the dream of an inland tour die? The explanations vary according to the person answering the questions. In 1986 Cairns told the Allentown Morning Call that he and Plarr wanted to run the event again but needed first to make some modifications to the pool to improve the power of the waves. Karabasz said there was a specific reason that didn’t occur: Plarrr was upset at how the event was portrayed in the surfing press.

Jim Karabasz: ‘Why am I going to have these assholes back when they treated me like I was some sort of carnival side show.’ That is the gospel truth. It wasn’t logistics. It wasn’t for lack of interest. It was the fact that Bobby was like ‘I’m not putting my money up. Look at this childish press that I got when I’m trying to do something good for a sport.’

Why am I going to have these assholes back when they treated me like I was some sort of carnival side show?

Plarr has a more mundane explanation: profits. He said he had to eliminate surfing from the pool because it did not make sense to close it down for a small group of surfers when thousands of people a day wanted access to it.

Robert Plarr: I wasn’t upset.

He did as much as he could to pull the event down as anything else.

Karabasz is still peeved at how certain journalists covered the event.

Jim Karabasz: Had people like Mr. George been a little more open minded and a little less arrogant there probably would have been a second Inland Pro Surfing Championship.

Matt George: I was brutal. That was my take. I was brutal. And I am happy with that. I had surfed all the wave pools of the world. I was interested in artificial waves since I first started surfing at 8 years old. I had built wave pool models myself made out of coke cans filled with sand. I was a believer, man, which is why the disappointment was so powerful.

Shaun Tomson: The dream of man made waves burst at Dorney Park.

Ian Cairns: Rightly so the event got portrayed as being held in crappy waves. It wasn’t big enough it wasn’t powerful enough. I’m stoked we had the opportunity. I look at Dorney Park and say wow we had the first event in a wave pool ever. I mean, it was amazing. It was a window in time whose idea will come.

Robert Plarr: I was the guinea pig and it worked out. Nobody else believed it. Only my own insanity did it.

Ian Cairns: We tried it and it never happened again because the waves were just not up the standard. Here we are it’s 30 years later the waves are up to the standard. So the whole idea of the technology of making artificial waves didn’t die a death at Dorney Park. It just continued.

Matt George: I think every surfer on earth should send a thank you note to Ian Cairns with a check for 5 bucks in it. His original vision has finally happened in his lifetime.

Could the future of wave pools look something like this? Illustration: Ignacio Serrano